Classrooms in South Sudan go silent as the Sun Stands Still

Submitted by fkakooza on

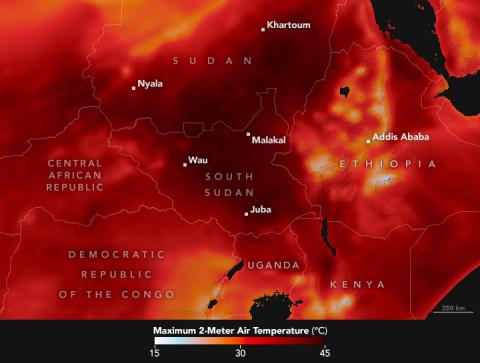

In March 2024, South Sudan faced an unprecedented heatwave, forcing the government to shut down schools nationwide, leaving both learners and teachers in limbo, unsure of when they would reopen. As the temperatures soared above 40 degrees Celsius, the heatwave was expected to last for at least two weeks, putting the country in a state of crisis.

In the two weeks that followed the closure, local media played a crucial role in reporting on this crisis, but mainly focusing on the event of the closure and not the underlying environmental and climate change issues. This later observation seems to cut across all local media, with the government owned ones rarely providing coverage while the local private ones being event-based.

This story documents how the media in the country captured and told the story, analyzing their factual accuracy, depth and quotes from key sources to reveal how they reported on this national emergency.

Eye Radio's coverage on March 17 was brief and spot citing the national government's directive to all state authorities to enforce the closure of all schools effective Monday 18th March, 2024 due to the excessive heat waves in the country. They quoted the Minister of Health Yolanda Awel Deng stating that the government has decided to close down all schools including “international schools, private schools, public schools, faith-based schools, all of them”. This use of a quote from the Minister lends the story credibility though the lack of depth about the heat wave’s broader implications is quite noticeable. And so is the missing voices of those affected by the heatwave.

Adom Online, an online based news site did slightly better than Eye Radio, telling the story of school closure in the context of the broader humanitarian situation in South Sudan. They quoted Peter Garang, a resident of the country's capital, Juba who openly welcomed the government's closure of schools. He advised as stated “schools should be connected to the electricity grid to enable installation of air conditioners”. The inclusion of a resident's perspective adds a human element to the story. The story is however shallow on the effects of the crisis as well as the broader issues around it. This kind of reporting appears to be becoming a trend.

For Radio Tamazuj, there was an attempt at providing a detailed overview of the heatwave's impact on South Sudan as a country and its people quoting, again, the Minister of Health Yolanda Awel who said “heat waves can have acute impacts on the population within short periods often leading to public health emergencies and increased mortality rates. As covered in this article the Minister added that events of the heatwave trigger socioeconomic consequences such as reduced work capacity and productivity as well disruptions in the health service delivery.

Radio Tamazuj's coverage also warned of the unprecedented climate change effects in South Sudan in the near future including heavy rains, floods and drought as stated by John Africano Bartel, Undersecretary for Environment in the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The story gives a lot of space to the Minister thus providing the government view as the main narrative. This points to the problem of tensions in the relationship between the media and the government.

Radio Miraya, a United Nations radio, gives an informative coverage but lacks analytical depth and so doesn't cater for those seeking a deeper understanding of the crisis. This may be understandable considering the fact that not so long ago the radio was shut down briefly for toying a line that was viewed by the government to be anti-establishment.

The Sudan Tribune coverage focused most on the heat wave impact on students(children) but quoted, as expected, the government sources including the Deputy Minister of Education Martin Tako Moyi. The story however highlights the parents’ role in the safety of children during the crisis as they are cautioned to keep the children indoors and as monitoring them for signs of heat exhaustion, though the parents’ voices are missing. It is also shallow on the wider aspects of environment and climate change.

It is France 24 whose coverage included footage of empty classrooms, residents lining up with jerry cans to buy ice, interviews with teachers all aimed at bringing out the impact and reach of the crisis onto the people. One of the interviewees, Anthony Moi-Alamin a school Principal stated: “children are sweating in the class, teachers are also sweating and they all can't settle in class”. This therefore explains the empty classrooms as earlier covered and portrayed in the video.

Additionally, Joseph Pompeyo, a school teacher in Juba stressed that in the past temperatures of Juba weren't as they are of late, they had a lot of “neem” trees but because of the war, most of the trees were cut down for firewood and charcoal.

This coverage utilized audiovisual storytelling telling, the interviews included personal stories of those affected such as learners and teachers.

The above coverage creates a dichotomy between the local media channels are cautious and shallow in covering the issues and the international media that go in and tell detailed stories. However, the international media such as France 24 emphasises the angle of the victims as opposed to the local media that tell the government narrative.

Under the circumstances, the media in South Sudan has played a commendable role in informing the public about the closure of schools caused by the heatwave crisis and its repercussions. But the wider issues around the subject remained largely untouched.

- 389 reads